Introduction

In 2001, the government of West Bengal, run by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), decided to legally change the name and spelling of the city of “Calcutta” to “Kolkata.” The difference between the two names is a matter of phonetic pronunciation. The first indicated the spelling associated with the English pronunciation of the city, as determined by the British colonizers, and the latter indicating the Bengali pronunciation of the city name. This is important to note for a few reasons: first, although 2001 marked an official legislative change, following similar changes in other Indian cities, such as Mumbai (formerly Bombay) or Chennai (formerly Madras), it did not change much for Bengalis who were already used to referring to the city as “Calcutta” when speaking in English and “Kolkata” when speaking in Bengali. Second, the new name was intentionally representative of the original Bengali pronunciation, thus acting as a rejection of the anglicized aspects left behind from the era of the British raj. In that same year, as the city’s name changed to become “more Bengali,” the West Bengal Heritage commission was formed to take on issues of heritage conservation in an institutionalized, state specific manner, independent from the preservation decisions being made at the national level. These two seemingly separate changes at the turn of the millennium both triggered (or were, perhaps, triggered by) questions of identity and nostalgia amongst Bengalis, particularly the role that colonial legacies played in each. Though this phenomenon is not specific to Calcutta, this article strives to show why it has been so difficult for this city, in particular, to rid itself of its coloniality, and the ways in which that struggle is shaped by the institution of preservation.

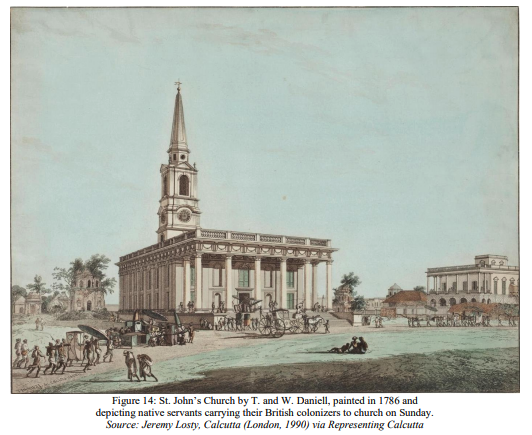

For more than two centuries, Calcutta had benefitted from being the second city of the British Empire, only after London, which made it the urban epicenter for the concentration and dissemination of Western culture in the East. As a colonial capital, the city enjoyed a level of economic prosperity, political power, and cultural clout which fostered a sense of entitlement amongst elite Bengalis that thrived under such urban conditions. This article investigates how and why the Bengali Bhadralok (elite class) have utilized historic preservation over time to perpetuate the conceptions of value and narratives of power that originated during the British colonial project and gifted them their standing, thus assuring a global recognition of their elite status as well as Calcutta’s colonial glory.